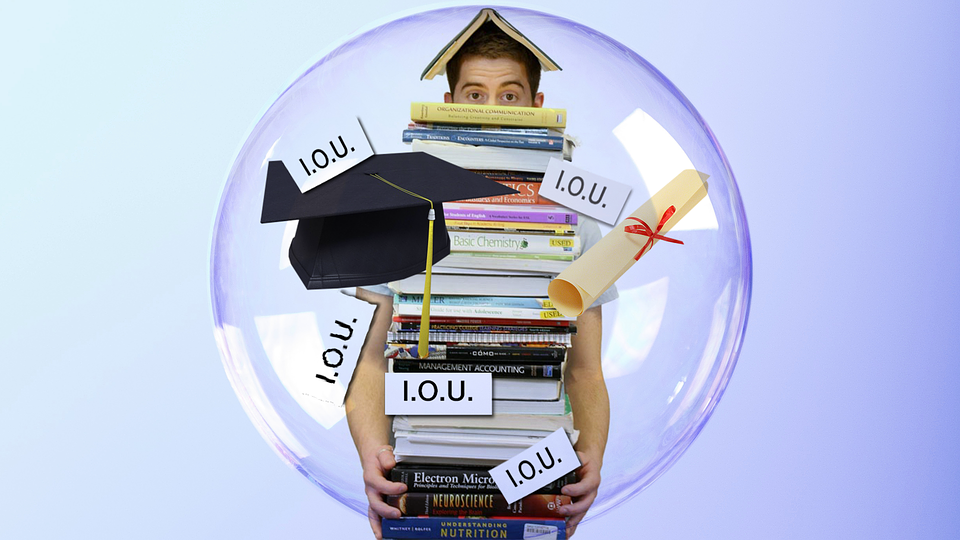

Should we be exporting a broken model?

Lately, there is a lot of media discussion on the student loan crisis in North America. With documentaries, tech startups, a US government task force, and an endless stream of articles decrying the current state of affairs with student loans, it’s understandable that a lot of well-meaning individuals ask:

“There is a student loan crisis in the US. Do we really want to export that model to the developing country and allow private investors to reap the returns?”

Rather than employ the same broken model that exists in North America we are employing a new model that aligns the interests of lenders, students and universities.

Federal student loan debt in the US has more than doubled in the past decade, while new graduate wages have stayed relatively flat.

It might make more sense to think of our model as an equity stake in students: we provide complete support for 4 years of education (tuition, housing, and a living stipend), and after graduation we take a percentage of their income for a set period of time. If they do well, our investors do well. If the student doesn’t do well we are motivated to assist them on the path to gainful employment.

The percent of income repayment model we're using, also called income sharing agreement, was pioneered by other lenders working in developing countries. It ensures that students won't be stuck with a burdensome student loan debt--if they can't find work they aren't obligated to repay us. And if the student for some reason doesn't earn a multiple of the poverty line they also aren't required to repay. The ROI to our investors is high, but the ROI to the students is many times higher.

We believe that an education should be available to anyone, regardless of their family/income status. Our model allows us to accept students whose parents are unbanked and unemployed--as long as the student has the required grades/scores we will accept them. The bulk of our students come from poor families and without our support would not be attending college.

And inevitably, a second counter comes back: “But shouldn’t we rely on scholarship funds to cover the shortfall?”

We estimate there are over 60 million students each year who graduate from a high school in the developing world with the grades, talent and ambition to attend college, but don't attend due to insufficient funds. Educating these students requires many billions of dollars, and is one of the largest value creation opportunities of our time.

We've seen first hand how scholarships can change the lives of the small percentage of students who receive them. But at the moment, there simply isn't enough capital flowing into scholarship funds to make a sizable dent in this capital shortfall. The only way to marshal the necessary capital to solve this problem in a meaningful way is to help traditional, profit-seeking investors understand that backing the leaders of tomorrow is a sound financial investment.